Lunch with Jan Wong and Maxine Ruvinsky: a conversation about the Stratford Cullitons and its rape scandal

By Grant Fleming

Recently, I talked with two prominent journalists and teachers, Jan Wong and Maxine Ruvinsky, about a scandal involving the junior hockey team in Stratford, Ontario. Before I get to that interview with Ms. Wong and Dr. Ruvinsky, here’s a recap of the story:

On October 3rd, 2014, Mitchell Vandergunst, an assistant captain for the Stratford Cullitons team, was convicted on two counts of sexually assaulting a woman. His case dated back to a series of incidents that occurred in July 2013, in South Huron, Ontario – less than an hour’s drive from Stratford. His 10-day trial ran from March, 2014, to the day he was convicted in a courtroom in nearby Goderich, Ontario.

Hours after the judge pronounced Vandergunst guilty, his team, the Stratford Cullitons, allowed him to lace up his skates and play. He went on to compete for the Cullitons for another four months.

In late January of this year, the father of the victim called the editor of the Stratford Gazette newspaper to complain. The dad and the mom wanted to know why the team was allowing a convicted rapist to carry on with his life while their daughter was trying to rebuild the shattered pieces of her own.

The editor called the team’s president, Dan Mathieson. He asked what he knew about Vandergunst’s sex crimes. Mathieson, who is also the mayor of Stratford, said he knew nothing.

On February 5th, Mathieson and his fellow board members kicked Vandergunst off the team. The announcement came two days after Vandergunst was sentenced to one year in jail plus two years of probation (he’s appealing). Mathieson told reporters that the coach, Phil Westman, resigned willingly that same day.

At the news conference, Mathieson offered few details about Westman’s role in concealing Vandergunst’s crimes, but he told reporters that no one else with close ties to the team, including board members, knew about the convicted rapist in their midst. Mathieson has since refused to answer questions about the scandal. Westman isn’t talking, either.

That’s the summary. This site contains much else to read about the scandal(including the Resources and FAQ sections).

Here are the two journalistic leaders who have a few things to say.

Maxine (“Max”) Ruvinsky is a pioneer in Canadian journalism. In 1999, she co-founded the journalism program at University College of the Cariboo (now Thompson Rivers University), in Kamloops, B.C. She served there as Professor and Chair until her retirement this spring. Before her life as a teacher, Dr. Ruvinsky worked as a newspaper reporter, including for seven years at The Canadian Press. She is the author of four books, including the groundbreaking book, Investigative Reporting in Canada (2007, Oxford University Press). Read her biography here.

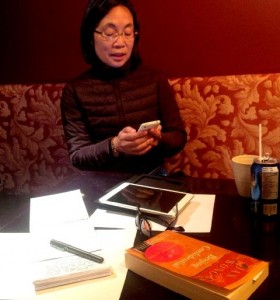

Most readers will know who Jan Wong is. She’s one of Canada’s most decorated journalists and a bestselling author of books such as Red China Blues (1996, Bantam Books). She knows about stories involving athletes and their roles in the culture of rape (more on that later). Ms. Wong’s even taken a bus ride with junior hockey players. These days she teaches journalism at St. Thomas University, in Fredericton, N.B. Here’s her bio.

The three of us got together a few weeks ago – sort of. I lunched with Ms. Wong while Dr. Ruvinsky joined us by phone from Kamloops. We talked for several hours, and then we followed up with calls and emails.

As mentioned, we focused on the scandal in Stratford (we even debated if it’s a scandal, a cover-up, or a shove-under). We also talked about the role of the media in covering such stories. The public’s appetite for serious journalism (do people care?) came up, too.

Here’s our conversation:

The club president, Dan Mathieson, who’s also the mayor of Stratford, said the only person who knew about Vandergunst was the coach. What do you make of that?

Ruvinsky: Mathieson’s claim that the now-forced-out coach was the only one who knew is a touch too convenient.

Mathieson said the coach told him that he kept Vandergunst’s rape conviction a secret because he thought a publication ban protecting the victim’s identity prevented him from doing so. Plausible?

Ruvinsky: If what Mathieson told reporters is an accurate account of his conversation with the coach, that the coach thought the ban applied to the perpetrator, that’s unbelievably stupid.

I’m guessing that most people who have concerns about this scandal would think that the coach should have consulted with Mathieson or the team’s lawyer. Again, though, we’re only going on Mathieson’s version of events.

Wong: The coach was under no obligation to be quiet. On the contrary, he had a duty to tell the board and the rest of the team and their parents. The publication ban is only for publications.

Ruvinsky: I find it hard to believe that the coach acted on his own. It would be interesting to know what the coach is doing now. Is he still in town?

The ex-coach lives in a small town north of Stratford. I went to his door in late March. He was in no mood to talk. One thing he did say was that the team put him in a “very, very bad position.”

Ruvinsky: Perhaps the team greased the coach’s un-protesting exit with an offer of alternative employment or an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Mayor Mathieson now refuses to answer questions. What’s your take on that?

Ruvinsky: Why am I not surprised? Only I wouldn’t call it a conspiracy, necessarily. After all, no conspiracy is required to conduct business as usual—and that’s certainly what this cover-up amounts to. On a journalistic level, the fact that he now refuses to answer questions simply reinforces that he does indeed bear responsibility for the cover-up – or the shove-under.

Wong: Well, he was always in silent mode. It’s just that you’re now poking him, so he’s gone deeper under. By the way, who besides Mathieson runs the team?

The board of directors has 25 members. Of those, 24 are males.

Wong: Wow, one non-male?

Yes. Back to Mathieson. I’ve lost count of the number of people in Stratford who’ve said to me, and I’m paraphrasing here: ‘The one person you should believe is Dan Mathieson. He’s a good mayor.’ What should a reporter do with those opinions?

Ruvinsky: As a reporter, I would trust the facts, not anecdotes and opinions, no matter how well-regarded those sources are. Especially because Mathieson is such an influential figure, I would try to catch him in a lie. So I would proceed to try to corroborate sources, and when I found, as you have, the relevant inconsistencies, I would interview Mathieson again and ask him questions, like a good lawyer would, to which I already knew the answers. Then I would publish the story and let them howl.

Wong: Believe the mayor? Of course you do not believe politicians. Your professional job is to question authority.

What would you tell your reporters if you were in charge of the local newsroom?

Ruvinsky: I would put my best reporter on the case and support that reporter with everything I had, including, of course, my advice. If I were unable to do that because of political pressure, I would resign from the editing job.

You’d resign? Why?

Ruvinsky: Simple. If I’m undercut as the newsroom leader, I have no future there. Best to get out, and then, I don’t know — write a book? Or start a blog!

The team’s board also includes a vice president who was once the police chief for Stratford. He won’t talk. Also, there’s another Stratford police officer connected to the Cullitons team. He’s still active on the force. The Cullitons website lists him as the prevention services coordinator. He told me he had no comment. What does that tell you?

Ruvinsky: Cops who won’t talk — another surprise. Cops and their connection to hockey — no newsflash there.

Also, the team’s website lists a hockey trainer whose day job is working as a cop for the Ontario Provincial Police. That’s the force that arrested and charged Vandergunst. I phoned him recently, but he hung up immediately after I told him why I was calling. I left him a message. No response.

Wong: The next move for any reporter would be to dig some more. With Mathieson and his board members and staff, including those cops, you obviously need to find proof that they knew and didn’t do anything. But I always start by never taking a politician or cops at their word. It’s like what I tell my journalism students, when your mother says she loves you –

Ruvinsky: — check it out! [laughs]

Wong: Exactly! Get another source. I didn’t make up that line, obviously. Max knows!

By the way, the governing body – the Ontario Hockey Association – won’t answer questions about a convicted rapist continuing to play. What do you make of that silence?

Wong: From the perspective of the team and league officials, it’s flat-out unethical.

Prominent people in Stratford, including one who’s had close dealings with the hockey team, told me, ‘I hear she’s a tart.’ He was referring to the rape victim. Others have spread gossip that the victim’s having doubts and wants to recant.

Wong: That’s ludicrous. People have no clue how our justice system works, but they love to spread misinformation. It’s self-serving. Vandergunst has been convicted of rape, he’s been sentenced. The victim won’t recant. This isn’t a TV soap opera.

Also, a number of Cullitons players showed up at Vandergunst’s sentencing wearing their team colours, like they were making a show of force in front of the victim and her family. Mathieson likes to preach the importance of developing young men with “citizenship skills.” The company that sponsors the Cullitons offers the same assurance. But it was left to the Crown lawyer to tear a strip off them for coming to the courthouse in team jackets.

Wong: I’m not surprised. Rape culture means that people still blame factors like, ‘What was she wearing?’ ‘Did she send mixed signals?’ ‘Was she drunk or high?’ Rape culture downplays the seriousness of sexual assault. One result is that perpetrators aren’t treated the way we’d treat someone who stabbed someone. Reporters who cover cops and the courts observe that all the time.

Also, team sport gets conflated with boosterism, whether it’s on a high school level, a town level or a national level. To attack a team or a hockey player is to be unpatriotic.

Max, you recently said to me, ‘There are no heroes here.’ You were referring to the story of the Stratford Cullitons and Vandergunst. Actually, you said that the rape victim may be considered a hero. What did you mean?

Ruvinsky: I do think there are heroes to be found in these things. In my own experience, I could not have withstood the pressures of [reporting and teaching] without many heroes along the way. These people restore and help you maintain your faith – in the truth, that is, and the possibility of telling it. This is the sense in which I referred to the victim as a hero. How does a reporter find other heroes? He follows his nose and puts one foot in front of the other, and more often than not, the universe kicks in. People do care.

Let’s talk about the role of the media. Neither of the two newspapers in Stratford is covering the story. They showed up at Mathieson’s news conference three months ago, but then they dropped coverage. What do you make of that?

Ruvinsky: It’s a shame, and can be partly explained, I think, by two major trends in the newspaper business. One is concentrated ownership, meaning a lack of competition to get the story and get it right and get it first.

Two, there’s the rise of digital technology, which has both positive and negative potentials. In this case, the negative potential is that people are scanning the web and not reading newspapers. Even those who read newspapers online are a vanishing breed: most people are using the Internet to entertain and distract themselves, not in pursuit of serious journalism. When important townspeople see that they can get away with it, they are reinforced in their belief that they bear no personal responsibility and that the press has no teeth.

But I think most reporters are paralyzed by fear. They won’t act because they’re afraid.

What are they afraid of?

Ruvinsky: A mayor’s wrath. A mayor’s henchmen. A spineless boss. Hard work. Shall I go on?

I’ve heard from an editor at one of the papers. He told me he doesn’t have the resources to do investigative work on the Cullitons. Mind you, his paper is part of a big chain. What’s your response?

Wong: Lack of resources is not an excuse. Everything is a choice. You choose to put your time and effort into a serious story, or you cover quilting bees.

Ruvinsky: What resources does the editor think he doesn’t have? A backbone? A reporter with half a brain? No! This is not a question of lack of resources but of lack of political will and lack of a sense of personal, social, and of course, journalistic responsibility. The point is, lots of small papers do excellent investigative work, and all good journalism involves investigating.

I had a brief interview with a man here who’s the former managing editor of the Stratford Beacon Herald newspaper. He was the sports editor there before moving up. He also holds high-ranking positions in hockey and baseball in Ontario. I asked him, ‘If you were still in charge at the Beacon Herald, what instructions would you have given your reporters in terms of covering the Cullitons scandal?’ His answer was, ‘I don’t know.’ He scolded me for calling him out of the blue. What are your thoughts when you hear that?

Ruvinsky: There is no percentage for him to step on toes at his old paper. That’s one thing. Another thing is, I think it says clearly that he feels he has no obligation to care, no obligation to quality journalism, and no obligation except to his fellow clique members in Stratford.

Wong: I know what he would have done with the Cullitons story. He would have done nothing. And by the way, it’s fair for a reporter to call someone without warning.

The two papers in Stratford have quite a few sports reporters for such a small city. The paper of record, the Beacon Herald, employs a reporter whose main beat is the Cullitons hockey team. I’ve spoken with people who’ve asked, ‘How could he not have known what was going on with Vandergunst?’ Does that reporter need to report on what he knew or didn’t know?

Ruvinsky: I don’t know that the reporter needs to. After all, they got away with ignoring the story for some time now. If and when the big story about who knew what and when gets published, then for sure they will “need” to, in order to explain how the local paper of record either didn’t know – which, by the way, tells you what kind of paper it is: incompetent.

It should be pointed out that the reporter in question was also the sports editor – past tense. He’s been moved over to the news department.

Wong: Was it a voluntary switch? Who does he report to? When was the last time a sports editor got moved to news?

I don’t know why he was switched. He’s not talking.

Wong: As an editor, his duties include disclosing whether or not he knew. And if he did, why didn’t he report it? And if he didn’t, why is he so miserably uninformed?

Speaking of switching, let’s talk about the role of the public. Some people have told me they’ve heard this story over and over: hockey player rapes woman, rapist is allowed to keep playing, hometown fans keep cheering for rapist — nothing new here, let’s just move on. What do you make of that?

Ruvinsky: If that’s true in Stratford, it’s very sad, but it doesn’t change the job of journalists. If they can’t or won’t do their jobs, others need to step in.

Maybe Mathieson’s taken the temperature of his town. His experience tells him the public doesn’t care about who knew what, when they knew, and why they failed to act. He has strong evidence that his constituents trust him – he wins elections by landslides. Also, he knows there’s only one reporter covering the story. Hasn’t he got things figured out?

Wong: The public does care. They would care about their daughters, sisters, wives and mothers. But no one is telling them what’s happening. Also, he wins elections because no one with serious credentials cares to run against him. That’s a separate matter.

Maybe the media has their audiences figured out. For example, the two newspapers in Stratford know the public doesn’t care about reporting on serious matters. The public wants quilting bees and swan parades.

Ruvinsky: That may be what the papers think, but I do think some part of the public continues to care about investigative reporting. It doesn’t matter if this part is a distinct minority. All change was instituted by people who at the get-go held forbidden opinions.

But I also think newspapers are a bad example, because despite the clarion calls for quality as the way—and the only way—to win back a disenchanted audience and restore itself to its power and purpose, newspapers by and large haven’t taken up the challenge, except for The Toronto Star and so-called national papers, and they can’t do it alone, and in many cases won’t do it at all if it’s going to put them out of business.

I think that as newspapers fail and fall, investigative reporting will move to books and to new online venues. The evidence for this contention, at least in terms of books: the notable best-selling books of investigative reportage, including for instance Glen Greenwald’s No Place to Hide, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything – even though it doesn’t – [and] Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation.

I’m sorry, but I still don’t think the public cares about this story. They’re not calling the local papers demanding answers. I doubt they’re calling Mathieson. No one’s howling. Besides, why wreck the image of this great theatre town? It’s all about tourists coming to see Hamlet.

Ruvinsky: If the good townspeople care about their image and their bottom line, they would do well to earn a good rep by exposing and holding to account the wrongdoers among them, not helping to sweep the filth under the rug.

The proper job of journalism in the public interest is to seek and tell the truth without fear or favour, regardless of who likes it and who doesn’t. As we used to say in the 60s, the truth shall set you free, but first, it will probably make you miserable. So as a reporter, count on some misery, and if you can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen.

Another thing: the assumption that people haven’t cared enough to call up the editors is unwarranted. I think many people do care, but feel powerless to act. At the same time, the press cannot single-handedly solve the problems it identifies; this is one of the hardest things for good journalists to live with (and not become jaded and uncaring themselves). You could say to yourself, look, the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, the National Post, and many smaller papers, have been reporting on this issue for years now, and still nothing has changed. And there would be a large grain of truth in that appraisal, but where does such thinking lead the press and the public? To the very apathy we complain of. Positive social and cultural change takes time and people working together, but it’s still worth the candle.

Wong: The laziest position for local media is to report on quilting bees. Controversy sells newspapers, but it also gets you into trouble with the powers that be. Easier just to write about the quilting and go home when your shift is done. Most reporters are scare-dy cats.

Ruvinsky: The trouble is, people believe there’s nothing they can do, but they can. Look at it this way: you’ve got a lion tamer and a lion. We know when we’re watching this game that the lion is stronger than the lion tamer. The lion tamer knows that the lion is stronger. But the lion doesn’t know.

So journalists have to make a stronger case with the public – that’s what I’m hearing from you. How?

Wong: We’re at a juncture in journalism. The old media is dying and the new media is going to burst forward.

Two of my graduates from a few years ago came to see me recently. They’re both employed by major media organizations right now. They asked me, ‘What should we do in five years?’ I asked them, ‘What do you want to do in five years?’ They said they want to start their own newspaper. And I said, ‘You can do it tomorrow if you want, but I wouldn’t.’ I told them, ‘Cling to your old media jobs for as long as possible for training purposes. Take advantage of any expense account you might have, travel as much as you can.’

But then I said, ‘You can start this online newspaper right away. Work on it after hours. But you have to provide news. People will subscribe. And you should consider certain types of ads, which I think are possible if your paper’s hyper local. You have to make people want to come to your site. But remember, give your readers solid news and feature stories. Not the fluff at your full-time job.’

It’s entirely possible now – we’re seeing this kind of newspaper already – because we no longer need the printing press. In the old days you had to be a media mogul. You had to own a printing press and delivery trucks. Now you just need an iPad.

Ruvinsky: The business of journalism needs to be re-invented. I’ve got several ideas.

Tell the truth and let the chips fall where they may…Let those who will cease to subscribe or advertise do so, and then publish a story in the last “post” about it before you turn out the lights for the last time…Start a new online “newspaper” by subscription only – no ads – and market it to people who haven’t given up on life or love…Start an alternative “wire service” online — this was done in the sixties — it was called Dispatch News — and it was the first to publish Seymour Hersch’s My Lai stories, when the “straights” wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole…Start an independent freelancer’s association or go solo.

Also, I know a spot at the corner of St. Catherine and Atwater in Montréal where a lot of homeless people spend their days and nights. At least you won’t be lonely, though you could get murdered while you sleep . . . say in Winnipeg.

How the fuck should I know?

That’s it?

Ruvinsky: Get journalism students out of the classroom where they talk about shit they couldn’t care less about. You put them with a teaching newspaper where they learn about journalism by doing journalism. The Times newspaper in Tampa-St. Petersburg (Florida) is an example. The editors there are teachers, too.

But you need to have journalists who are interested. They need to be willing to work together for a common cause. You have to have evolved people. You can’t have what you have now – scared little rabbits.

And as for readers, it’s always the vanguard you’re going after. They’re out there. They want good journalism. Social change is always led by a small percentage of people. But give it time. People will buy in, even if they do it slowly.

Talk to me about investigative reporting. What’s it worth to the public?

Ruvinsky: Something people in the business have been saying for decades is that investigative journalism is all very well, but if all you ever do as a reporter is tell people one more thing that’s horribly wrong that they can’t do a damn thing about, people are going to phase out, because everybody’s got problems. Nobody wakes up looking for problems they can’t do anything about.

Investigative journalism has to move forward to offer solutions. I just can’t report on the bad guys like the ones you have in Stratford with the hockey team. We’re all bad guys, and we’re all good guys. The only hope for us humans is to make some kind of common cause based on reasonable communications with each other.

Wong: Oh, yes, investigative reporting matters. But I think you can get this paralysis if you report on things that have nothing to do with the readers’ lives. But if you report on stuff that directly affects them, they’re going to read it.

Now you’ve got me thinking about a TV station in Kitchener. It thinks investigative reporting begins and ends with telling its viewers that the cost of weddings may be a rip-off.

Wong: Oh, really? Well, people want to know when it involves their money. Weddings can be a rip-off.

Okay, let’s go with that. Moving along – what’s the investigative reporter’s role in finding solutions?

Wong: I think reporting the fact of the sexual assault involving the Stratford hockey player is necessary, of course, and it’s necessary to report on the cover-up. But you don’t have to find solutions, necessarily. Max may disagree with me.

Ruvinsky: Yeah, but people want to know they can do something about the problem.

Wong: I think the very active reporting on what happened – the assault, the attitudes and silence of the people in charge of the team – is a journalist’s role. You’re shining a light on it. By doing that, you’re probably going to save young women. You’re probably going to spark conversations at home involving hockey players and their parents and their sisters and their girlfriends. I don’t think it’s for nothing.

Let’s circle back to the Stratford hockey player who raped a woman? How do you know the public will take notice and talk about it?

Wong: Here’s my evidence. A group of journalism students I teach at St. Thomas University ran a rape story this year involving a male varsity athlete. We had six young women come forward. Three of the women were willing to be named.

What we found is, the women got complete support. We were expecting hate mail. We were expecting a backlash. We didn’t get that. Not only were the victims okay, but their huge, vast circle of acquaintances were getting in touch with them to give their support.

Another thing we found was that another half a dozen new victims came forward. They contacted the first group of victims and said, “it happened to me, too.”

So, yes, you will spark a conversation.

Ruvinsky: You might spark a conversation, but it might be short-lived.

Here’s what I mean about moving forward with solutions. It’s not a matter of ‘here’s the answer on your math test.’

Let me give you an example. After you finish with the story of Vandergunst being allowed to play on the hockey team after he raped a woman – once you break the silence and find out who knew what, and when – you could call Vandergunst’s father. You could ask him if he was concerned at all about the moral development of his son. Isn’t he appalled? Isn’t he worried? Doesn’t it bother him? You could also talk to a psychologist. Those kinds of stories.

We’re wrapping up here. Max, what’s your number one message to your journalism students?

Ruvinsky: If you know this is the work to which you want to devote yourself, then do your homework, never stop learning or loving, park your ego at the door to the story and proceed in good faith. Be not afraid. As far as I know, it’s still the best work in the world, writing that first draft of history, a ringside seat. If you don’t want to do this work, find something you love and believe in, and devote yourself to that. More important even than what you choose to work at is how you choose to work at it. In other words, with passion and integrity, let’s hope.

Jan, what’s your message?

Wong: Question authority and burn your bridges.

Explain that, please.

Wong: Burn your bridges means don’t try to suck up to your sources or hold back anything out of fear you’ll offend someone and they’ll stop talking to you. What good is it if they talk to you and you can’t print it? You’re only as good as your last story.

Thanks, both of you.

Wong: You’re paying for lunch, right?

(Note: A few days after we talked about ways and means to train journalism students to become better investigative reporters, this story about an award-winning proposal to do just that appeared in the news. Wong and Ruvinsky emailed me to say how excited they were to hear about the initiative.)