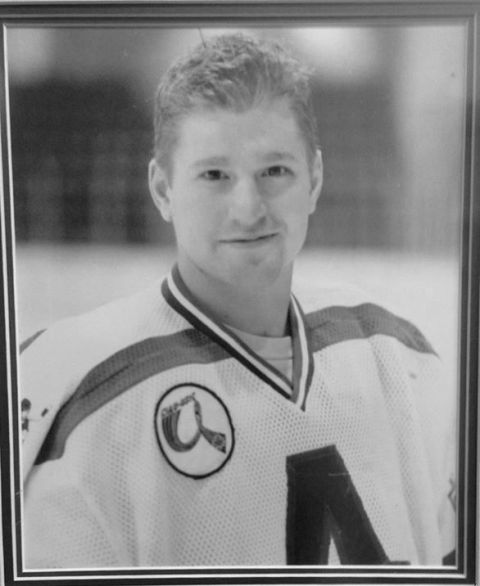

Kevin Powell: A hockey hero who spoke truth to power

A story to share about Kevin Powell, and something I just learned about him. Most of you, possibly all of you, won’t know about him.

I spoke with Kevin, by phone, one night in January, 1997. I was in Regina, Saskatchewan, working as a sports reporter for CBC Radio. Kevin, who was 23 at the time, was studying and playing hockey at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. What he said that night was explosive.

Kevin told me that a number of prominent citizens of Swift Current (Saskatchewan) allowed a high-profile hockey coach — the now-notorious sexual predator, Graham James — to run amok. James raped and molested teenaged boys who played for the city’s junior team, the Broncos.

By going public with the shocking revelation, Kevin joined forces with two other courageous men: Darren McLean, and another ex-Swift Current junior hockey player whose name remains protected by a judge-ordered publication ban (he was one of James’s sexual assault victims). The three played together in the early 1990s, years after James’s better-known victims, Sheldon Kennedy and Theoren Fleury, starred in the Western Hockey League.

I remember how I came to speak with Kevin. Darren McLean led me to him. Before doing so, Darren had given me detailed and extraordinary information of his own — on the record — about what went down in Swift Current.

“A bunch of us players called a meeting with the brass. We told them what Graham was doing,” Darren recounted. The people in the room included several senior executives for the community-owned team, including the president. The results were disastrous for the players.

“They didn’t do anything,” Darren told me. “Well, they went back and told Graham what we said. Graham went berserk. A bunch of the players got scared and backed down.”

Darren paid a steep price for his honesty. He described how James instructed those same Bronco executives to hand him an envelope of cash the day after the meeting. They told him to leave Swift Current on the next bus.

I couldn’t run the story unless someone corroborated what Darren told me. I asked him to give me names of teammates.

“Call Kevin Powell. He’s a straight shooter and a good guy. Tell him Darren says hey.”

Kevin Powell’s parents lived in Regina. I phoned them to get a number. His father, Grant, encouraged me to make the call. (“I’m not positive, but Kevin might talk to you.”)

I reached Kevin that night. He didn’t hesitate.

“What Darren told you is true. We told those execs about Graham,” Kevin said. “Anyway, we could tell they already knew. But they pretended not to. It was a joke.”

Kevin named names. Not just team executives for the Broncos, either. His list included a prominent lawyer in Swift Current as well as the local high school guidance counsellor.

What an interview. Kevin was courteous, uncommonly candid, and thoughtful. Also, he exhibited a joking manner. (“It’s about time one of you reporters called me.”) It would be the only time he and I spoke. I had my story.

(The bonus: a day later, the third young man, the one who can’t be named, confirmed what Kevin and Darren told me.)

I was thinking about Kevin last night, wondering what became of him. I went to the website for the Acadia University athletics department, and found this:

An endowed award was established in 2004 by Joyce and Grant Powell and family in memory of their son Kevin who was a member of the Acadia Axemen hockey team from 1994 to 1998. Kevin died suddenly during June 2002, in a motorcycle accident.

This morning, I called Kevin’s parents, Joyce and Grant. They still live in Regina, both retired. We chatted for about 30 minutes. Grant didn’t remember the day I phoned him in the winter of ’97 (“eighteen years is a long time ago”), but the two of them didn’t seem to mind a cold call from Stratford, Ontario. (“We’ve travelled all over Canada, but we haven’t made it there.”) They talked about Kevin’s life and legacy.

“There was the hockey part of his life,” Grant said. “That’s the part where guys don’t talk much. They keep things to themselves. We didn’t know a lot about those days in Swift Current.”

I mentioned to Grant that his son helped to break the silence about the horrors that went on in Swift Current.

“That’s true,” he said. “Kevin was a –”

I could hear Grant’s voice catch. He was fighting to maintain his composure. I was, too. Joyce jumped in just in time.

“There was the other part. Kevin was always very kind,” she recalled. “He was always mowing people’s lawns as a kid, including his grandparents. And he did something else that many young men wouldn’t do. He’d babysit other people’s kids. He was a caring person.”

I asked Joyce and Grant if they thought Kevin made a difference, if people in Swift Current, especially the leading citizens and Bronco officials, learned anything.

“I don’t think so,” Grant told me. In fact, a number of Bronco officials who knew about James, including the chairman of the board, would remain with the team for many years.

Did the Broncos ever do anything to pay tribute to Kevin?

“Not that I’m aware of,” Grant said. “But he only played one season there.”

We had to wrap up our conversation. I didn’t get a chance to ask Grant and Joyce what happened to Kevin once he moved to Calgary in order to start the next chapter of his life. Instead, they finished on a high note by talking about the Kevin Powell Memorial Award, the annual bursary they set up to help student-athletes at Acadia University. It’s not the only reminder of their son’s extraordinary life, either.

“You know, Acadia also retired Kevin’s hockey sweater,” Joyce mentioned.

“It’s hanging up in the rafters,” Grant boasted.

(Read Kevin Powell’s obituary here.)